The latest location battling to legalize medical marijuana is not where you’d expect.

Come voting time this fall, Arkansas will be the first Southern state to ask voters whether to legalize medical uses for pot.

The move would be a rare opportunity for supporters of legalizing the drug to tap into a region that has resisted easing any restrictions on the drug.

The state’s top elected officials and law enforcement agencies oppose the idea, but legalization groups hope the referendum shows that medical marijuana is no longer solely the domain of East Coast or Western states.

“This is an issue that hasn’t been ready for primetime yet in the South. It may be that it’s starting to be, and that’s a good thing,” said Jill Harris, managing director of Drug Policy Action, the political arm of the Drug Policy Alliance.

The South and Midwest have remained mostly on the sidelines in the nation’s marijuana-reform movement, which will also put proposals for full-scale legalization before voters this year in Colorado, Oregon and Washington state.

So far, 17 states and the District of Columbia have legalized medical marijuana in some form. Massachusetts voters are expected to vote on it in November, and another measure could appear on North Dakota’s ballot.

Past efforts to put medical marijuana on the ballot in Arkansas have faltered, though voters in two cities in the state have approved referendums that encourage police to regard arrests for small amounts of marijuana as a low priority.

Supporters of the current proposal mounted an organized and well-funded campaign that surprised many political observers. Arkansans for Compassionate Care, the group advocating for the measure, won ballot access after submitting far more than the required 62,500 signatures.

Medical marijuana has never come before voters in the South partly because of the difficulty of getting such initiatives on the ballot. And conservative legislators throughout the region have not backed the efforts. That’s why the Washington-based Marijuana Policy Project spent more than $246,000 on the Arkansas initiative and is expected to spend more.

The national group stepped in after polling showed strong support for the measure in Arkansas. Group leaders also cite a “symbolic” value in passing medical marijuana in the South.

“For some reason, public officials have been way behind public opinion on this issue,” said Morgan Fox, communications manager for the agency. “Politicians are starting to realize that they don’t have to worry about backlash.”

Backlash over marijuana is nothing new for Arkansas public figures. The state’s most famous political son, former President Bill Clinton, was ridiculed during his 1992 campaign for admitting that he used marijuana in college but insisting he didn’t inhale.

And Joycelyn Elders, the Arkansas doctor who was named by Clinton to be surgeon general, drew criticism in office for suggesting that drug legalization should be studied. Elders, who is now an outspoken advocate of marijuana legalization, said she believes the Arkansas effort could pass with a strong education campaign.

“If we educate the people in Arkansas, we can do the right thing,” Elders said.

Lacking any big-name supporters and facing opposition from some of the state’s top elected officials, Arkansans for Compassionate Care is turning to patients in its campaign.

Kathy Reynolds said she used marijuana in 1992 to help her eat after undergoing breast cancer treatment and bone marrow transplants. Now 57, she says she would like to use it again to dull the pain from a degenerative bone disease. But she’s worried about being arrested.

“I’m afraid to,” Reynolds said. “The risk it would be to use it at this point outweighs the benefit.”

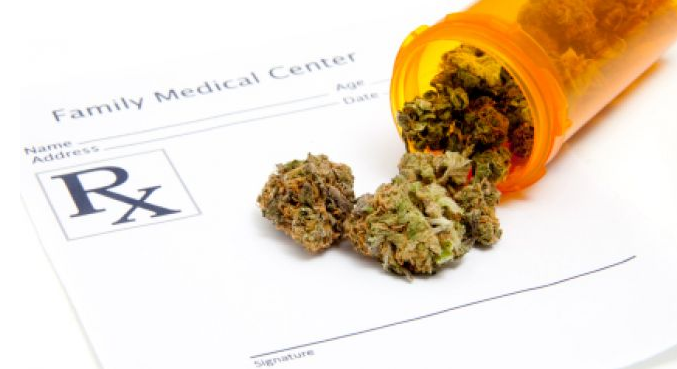

If approved, the Arkansas proposal would allow patients with certain qualifying conditions to use marijuana with a doctor’s recommendation. Qualifying conditions would include cancer, glaucoma, HIV, AIDS and Alzheimer’s disease.

Nonprofit dispensaries would be allowed to sell pot. But if patients live more than five miles from a dispensary, they or their caregivers could also grow marijuana.

The ballot measure’s future isn’t guaranteed, however. A coalition of conservative groups has asked the state Supreme Court to strike it from the ballot, claiming it misleads voters.

Even if it’s approved, federal prosecutors could shut down any dispensaries, as they have in other states. Arkansas Attorney General Dustin McDaniel said the conflict with federal law is one of the reasons he opposes the measure.

Gov. Mike Beebe, another opponent, said aside from the federal legal questions, there are also worries about how much it will cost the state to regulate dispensaries.

“Those are serious questions, and a lot of that is unanswerable because you don’t know how many dispensing places are going to apply or going to be granted,” Beebe said.

Even some of the state’s medical marijuana supporters are somewhat wary of the proposal.

State Sen. Randy Laverty, who said he generally supports medical marijuana, said he’s undecided and wants to review the proposal to make sure any dispensary system is tightly controlled.

“I don’t know if Arkansas is ready for medicinal marijuana or not,” Laverty said. “But if they are, I doubt they would want open dispensaries on the corners in various towns.”